Indian Women Hit Menopause 5 Years Earlier — Nutritionist Reveals How To Take Control Of Your Midlife Health

Indian Women Hit Menopause 5 Years Earlier — Nutritionist Reveals How To Take Control Of Your Midlif...

Nothing in life comes free, not even a sugar-free drink.

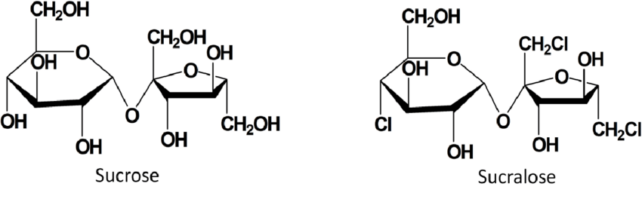

Scientists have now linked the artificial sweetener sucralose (sold as Splenda) to yet another potential health downside – and this time, the impact is not in the gut; it's in the brain.

In a randomized crossover trial, when a group of 75 adults drank a beverage containing sucralose, they showed heightened blood flow to the hypothalamus – a part of the brain that helps control appetite and cravings.

By contrast, when the same participants drank a beverage with sucrose (aka table sugar), there was a hunger-dampening effect. Peripheral glucose levels spiked, and this corresponded with reduced blood flow to the hypothalamus.

Two hours after drinking sucrose, participants reported significantly lower hunger levels than after they drank sucralose.

The findings, which are supported by initial research on rodents, suggest that non-caloric sweeteners may not actually be useful for losing weight or for reducing sugar cravings in the long run. In fact, they seem to change how the hypothalamus communicates with other parts of the brain.

Sucralose is 600 times sweeter than sucrose but with zero calories. This may create "a mismatch between the expectation of caloric intake and the absence of actual energy", the authors explain.

"If your body is expecting a calorie because of the sweetness, but doesn't get the calorie it's expecting, that could change the way the brain is primed to crave those substances over time," warns a supervisor of the study, endocrinologist Kathleen Alanna Page from the University of Southern California.

Page and her team say it is vital that the long-term health impacts of Splenda and similar sweeteners are investigated with further research, especially since as many as 40 percent of American adults regularly consume these sugar substitutes.

The recent trial included 75 participants between the ages of 18 and 35 who underwent three interventions each, receiving blood tests and brain scans before and after.

One day, they drank a beverage with sucralose. Another day, they drank a beverage with sucrose. And on a third day, they drank a glass of water. All the drinks had an unsweetened cherry flavor so the participants didn't know the difference. Each person served as their own control.

The order of the drinks was randomized for each participant, and the gap between sessions was anywhere from two days to two months.

Unlike drinking real sugar, drinking sucralose did not cause a spike in peripheral glucose levels, or hormones like insulin and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), which help control blood sugar levels.

"The body uses these hormones to tell the brain you've consumed calories, in order to decrease hunger," explains Page. "Sucralose did not have that effect – and the differences in hormone responses to sucralose compared to sugar were even more pronounced in participants with obesity."

This suggests that metabolic signals in the body are closely tied to brain activity. When sucralose interacts with gut microbes, for instance, previous studies have found it can impair the body's response to glucose. Perhaps this is also feeding into the unique hypothalamic response identified in the current research.

Once, Splenda was considered biologically inert, but recent studies have found concerning signs that this popular sugar substitute, often found in diet drinks and chewing gum, is linked to DNA damage, impairments in glucose tolerance, and an altered gut microbiome.

Two years after the World Health Organization issued a health warning about sucralose and its possible metabolic and inflammatory impacts, we have yet another reason to worry about consuming the sweetener willy-nilly.

Page and her colleagues are now conducting a follow-up study to see how sucralose impacts the brains of children and adolescents specifically.

"Are these substances leading to changes in the developing brains of children who are at risk for obesity?" asks Page.

"The brain is vulnerable during this time, so it could be a critical opportunity to intervene."

The study was published in Nature Metabolism.

Indian Women Hit Menopause 5 Years Earlier — Nutritionist Reveals How To Take Control Of Your Midlif...

Those who had their a surgery before the start of the weekend had an increased risk of adverse outco...